Reading from a Torah Scroll

On the ninth of Av, synagogues around the world remember the destruction of the First and Second Temples, as well as a litany of other Jewish catastrophes, from the expulsion of Spanish Jews in 1492 to the start of Nazi death camp deportations in 1942. At Beth Elohim in Queens, N.Y., the congregation adds one more date to the list: August 8, 1444.

On that day, Portuguese traders embarked from Africa for the New World with a shipload of human cargo. The event, which tradition marks as the beginning of more than 400 years of slavery, has singular significance at this synagogue, where everyone - the rabbis, the Hebrew-school teachers, the music director, on down to the last member - is African-American.

Way out in the St. Albans neighborhood - just take the subway to the end of the line, switch to a bus, and 20 minutes later, you’re there - the Beth Elohim Hebrew Congregation and Cultural Center occupies a storefront on Linden Blvd. It's nondescript except for the large Stars of David on the awning.

Rabbi Shlomo Ben Levy, dressed in a crisp, dark navy suit, red tie, and velour kipah, welcomes my friend and me at the door. "Shalom, Shalom," he says, in what I will soon think of as the community's signature greeting.

Inside, the long, narrow space resembles a modest synagogue sanctuary you could see anywhere. The mahogany ark, carved chairs and pulpit that dominate one end of the space were acquired from a synagogue in southeast Queens which was being converted to a church.

Biblical art and a backdrop of the Judean countryside decorate the walls. "It reminds me of my trip to Israel, right after the Six-Day War," remarks Lady Ann Dunbar, a synagogue member and a social worker with a master's from Yeshiva University.

About 40 people gather for services. While many of the men wear jeans and kipot, most of the women are in colorful African robes and headdresses.

Tonight's program, "The 16th Annual Tribute to the Ancestors Home Service and Lecture," is led by Assistant Rabbi Eliyahu (full name: Eliyahu et Hammurabbi Ras Yehudah), who makes a dramatic entrance in white Ethiopian robes and a goat hair hat. On other days, I am told, he may appear in a sharp modern suit or a red velvet garment festooned with Stars of David.

"Shalom, Shalom!" he chirps as others come up to greet him. "Erev tov!"

"The Torah gives us a way to commemorate slavery in Egypt, but we needed to create a ceremony to commemorate our slavery in this country," Ben Levy explains.

Beth Elohim is part of a loosely affiliated movement of Hebrew congregations in Brooklyn, Harlem, Philadelphia, Chicago, and elsewhere.

The website blackjews.org — administered by Ben Levy — claims there are approximately 40,000 African-American Jews in the United States. These are not the Ethiopian Jews one encounters in Israel, but Americans who have embraced this blend of Judaism primarily in the 20th century.

The black Jews observe most holidays, the rite of circumcision, and the laws of kashrut. God is invoked as Hashem; men and women sit separately on Shabbat; and when the evening begins with a rendition of "Hinei Ma Tov," the tune is the same one I learned in Sunday school and summer camp.

Unlike some more radical black sects that claim to be the only true Jews, these Black Jews - or Israelites or Hebrews, as they prefer to be called - see all Jews as co-religionists, despite differences in race and tradition.

In an essay on the website, Ben Levy admits that most of his flock is not Jewish according to halachah, but points out that fewer than 10% of the 5.3 million white Jews in America observe halachah themselves.

There is debate within this community whether conversion is necessary, with many claiming the doctrine of teshuvah (repentence) allows them to return to what they see as their original tradition.

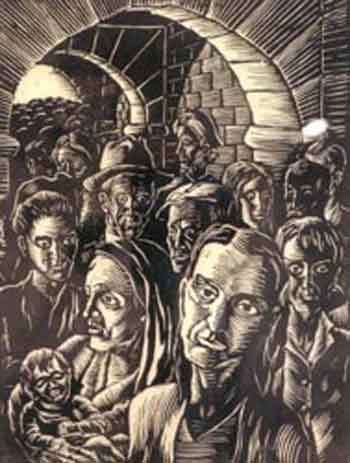

An Image called Bridges which featureds on a Essay

on African American and Jewish connections

Some, like Ben Levy, were born into the community - his late father, Levi Ben Levy, founded this synagogue in 1983 - while others have come from all walks of life.

Raphael Ben Dan, who serves as chief musician and has released a CD of original Hebrew songs, was born a Baptist in Ohio and converted first to Islam before finding his place among the Israelites.

A young man name Memelik, a student rabbi and guest speaker from Beth Shalom Congregation in Brooklyn, was born in London to Trinidadian parents. Another guest from Beth Shalom, Rabbi Yeshurun Ben Israel, was a city transit worker before attending the Israelite Academy, the Queens-based institute that ordains all rabbis in the community.

After a standing moment of silence to remember both the destruction of Solomon's Temple and the atrocity of African slavery, Ben Israel chants the "El Molay Rachamim." He begins in Hebrew but continues in English, the first and likely only time I will hear it this way.

And rather than the six million who died in the Holocaust, he invokes "the 100 million who passed through the Middle Passage" - the long, middle leg of the Europe-to-Africa-to-America slave trade route - an untold number of whom "may have been Israelites."

Dunbar then presents her lecture on the "psychosocial effects of slavery." She opens by pointing out that the first African slaves arrived in New Amsterdam in 1626, just two decades before the first Jewish refugees from Brazil. "And so the marriage begins," she says.

After Memelik reads aloud a few haunting facts and accounts of the African slave trade, the congregation rises as Ben Israel reads loudly from Deuteronomy, Chapter 28. To everyone in the room, it is clear that the Torah predicted the Middle Passage, or at least warned against it. "He will put a yoke of iron upon thy neck …" he intones and points to the poster pinned to the podium: a 19th-century daguerreotype of a slave on an auction block, his hands and legs chained, a large iron yoke around his neck.

The ceremony itself is uplifting, a symbolic display not unlike a Passover table. There are four colored candles, each representing an attribute of nature, and a seder plate-inspired selection of seven foods: bread, rice, fish, corn, boiled egg, parsley, and water, signifying everything from sustenance to the bitterness of 400 years of slavery.

"But 400 years can’t take away 40,000 years," Eliyahu exclaims. The point, he says, is to move forward from an enslaved mentality, to cast off that "chain on the brain." Judaism, he declares, is the answer.

"The Torah has the key to unraveling these problems," he exclaims, eyes wide. “And we even heard it in this week’s haftorah, remember? 'Comfort ye, comfort ye, give comfort to my people … proclaim that their service is at an end!' Isaiah said that. It’s all about moving on!" The woman next to me nods vigorously as she finds the passage in her Chumash (Five Books of Moses).

And so what began as a solemn evening culminates in something of a celebration — or rather, a kiddush, as Ben Levy leads everyone in hamotzi before volunteers pass out prepared meals consisting of all the ingredients mentioned in the ceremony.

"Remember, Torah is what it's about, and you all are the custodians of the Torah," Eliyahu tells me as we depart. "You kept it for 3,000 years. I tell my people to think about that. If it weren't for you, we never would have been able to discover it."

[A very insightful article written by Victor Wishna]

References:

Cleveland Jewish News: Another house of God: black Israelites find a home in Queens

BY: VICTOR WISHNA, Freelance Writer

Black and Jewish: blackandjewish.com

Cleveland Jewish News Thanks!

Cleveland Jewish News Thanks! : * black american jews * black jews * black Israelites * Beth Elohim * Rabbi Shlomo Ben Levy * Rabbi Eliyahu * Torah * Ben Levy * Black Jews * Jewish and Black * Israelites * Queens and Jews * Queens and Black Jews * Queens and Black Israelites * US Jews * American Jews * New Synagogue * New Synagogue and Black * Israel * BagelBlogger * Bagel Blogger

: * black american jews * black jews * black Israelites * Beth Elohim * Rabbi Shlomo Ben Levy * Rabbi Eliyahu * Torah * Ben Levy * Black Jews * Jewish and Black * Israelites * Queens and Jews * Queens and Black Jews * Queens and Black Israelites * US Jews * American Jews * New Synagogue * New Synagogue and Black * Israel * BagelBlogger * Bagel Blogger

Move your mouse over to display Bagel menu.

Move your mouse over to display Bagel menu.

Haveil Havalim

Haveil Havalim

Make a Donation thru Paypal

Make a Donation thru Paypal

0 Comments:

Post a Comment